Pin Up App

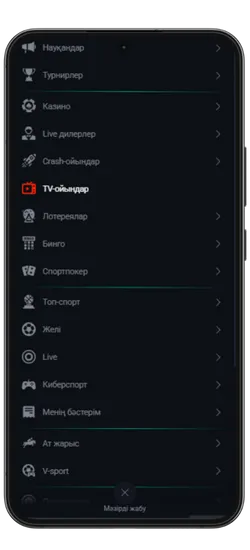

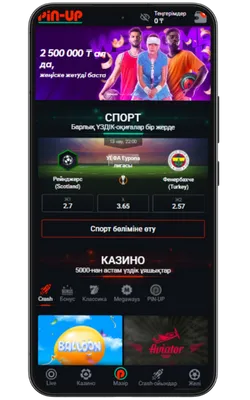

Біз Pin Up мобильді қосымшасын жасадық, ол казино мен спорттық ставкаларды бір ыңғайлы интерфейске біріктіреді. Қосымша Android және iOS жүйелерінде қолжетімді, VPN қажет етпейді және кез келген уақытта ойнауға мүмкіндік береді. Қолданбада сізді 10 000+ ойын, 50+ спорт түріне ставка жасау және комиссиясыз жылдам қаржылық операциялар күтеді.

| Pin Up Казино | Мәліметтер |

| 📱 Қолдау көрсетілетін ОС | Android, iOS |

| 🎲 Санат | Казино, спорттық ставкалар |

| 🔗 Жүктеу сілтемесі | Pin Up APK жүктеу |

| 💲 Жүктеу бағасы | Тегін |

| 📂 Файл өлшемі | 9.8 MB |

| 💰 Қош келдіңіз бонусы | 125% спортқа / 120% + 250 FS казиноға |

| 🌍 Тілдер | Қазақша, орысша, өзбекше + 12 басқа тіл |

| 📞 Қолдау | 24/7 онлайн чат, email |

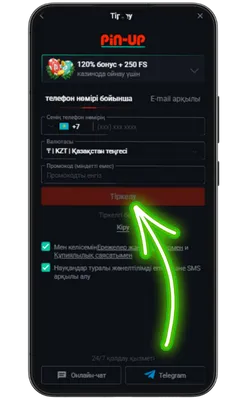

Pin Up KZ жүктеп алыңыз және 125% спортқа немесе 120% + 250 FS казиноға бонус алыңыз!

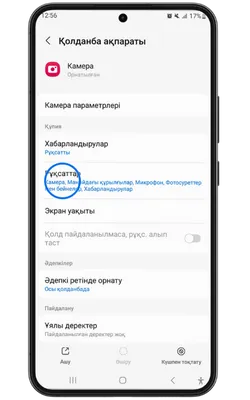

Қосымша үшін деректерге қол жеткізу

Pin Up Casino қосымшасы тұрақты жұмыс істеу, қауіпсіздік пен дербестендіру үшін белгілі бір рұқсаттарды сұрайды. Төменде қосымша ішінде пайдаланылуы мүмкін деректер келтірілген.

- 👤 Жеке ақпарат: аты-жөніңіз, email, телефон нөмірі – аккаунт құру және алаяқтықтан қорғау үшін қажет.

- 📍 Геолокация: нақты немесе шамамен орналасуыңыз – бонустар мен оқиғаларды дұрыс көрсету үшін қажет.

- 📸 Камера және фотосуреттер: камераға қолжетімділік – жеке басыңызды растау және құжаттарды жүктеу үшін қажет.

- 💳 Қаржылық деректер: төлем тарихы, реквизиттер – шот толтыру және қаражатты шығару үшін қажет.

- 🔑 Құрылғы идентификаторлары: құрылғы идентификаторы – аккаунтыңыздың қауіпсіздігін қамтамасыз етуге көмектеседі.

- 🔄 Әрекеттер тарихы: қосымшадағы өзара әрекеттесу туралы ақпарат – интерфейсті дербестендіру және сәйкес акцияларды көрсету үшін пайдаланылады.

- 📁 Файлдар және құжаттар: сақтау орнына қолжетімділік – қосымшаның жаңартуларын жүктеу және сақтау үшін қажет.

Біз SSL шифрлауды қолданамыз, PCI DSS қауіпсіздік стандарттарына сәйкестік сақтаймыз және пайдаланушының сұранысы бойынша деректерді жою мүмкіндігін ұсынамыз. Жеке деректеріңіз қорғалған және сіздің келісіміңізсіз үшінші тұлғаларға берілмейді.

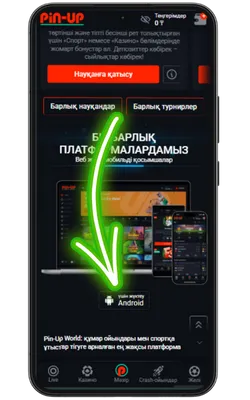

PinUp APK Android үшін

Pin Up Casino app Android құрылғыларына APK форматында қолжетімді және ресми сайттан тікелей орнатылады. Google Play қажет емес – жай ғана жүктеп алып, орнатып, ойнай бастаңыз. Төменде Pin Up қолданбасын телефонға тегін жүктеу бойынша толық нұсқаулық берілген.

-

Ресми Pin Up сайтына өтіңіз

Android браузерін ашып, ресми сайтқа кіріңіз және Pin Up APK-ның соңғы нұсқасын жүктеңіз.

-

Жүктеу түймесін басыңыз

Жүктеу бетінде «Pin-Up APK жүктеу» түймесін тауып, жүктеуді бастаңыз.

-

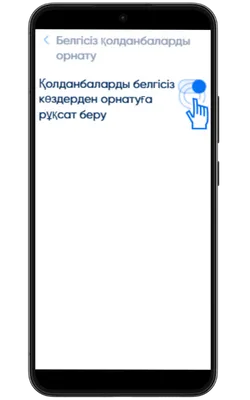

Белгісіз көздерден орнатуға рұқсат беріңіз

Параметрлер → Қауіпсіздік → Белгісіз қолданбаларды орнату бөліміне өтіп, APK жүктелген браузерге рұқсат беріңіз.

-

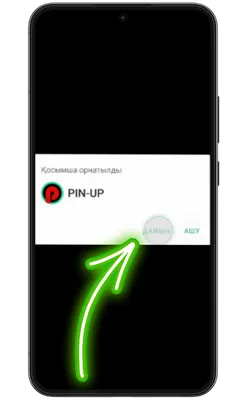

Жүктелген файлды ашыңыз

Құрылғыдағы «Жүктеулер» қалтасына өтіп, PinUp.apk файлын табыңыз. Орнатуды бастау үшін оны басыңыз.

-

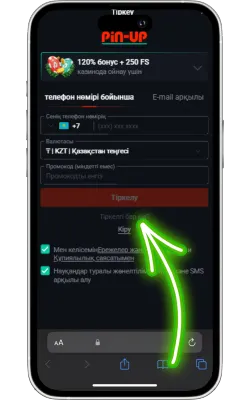

Қолданбаға кіріңіз

Орнату аяқталғаннан кейін «Ашу» түймесін басып, содан кейін тіркеліңіз немесе аккаунтыңызға кіріп, ойынды бастаңыз.

APK файлын қауіпсіз орнату

PinUp APK-ны тек ресми сайттан жүктеп алу ұсынылады, өйткені бұл зиянды файлдарды жүктеу қаупін азайтады. Біздің APK файлы тұрақты түрде қауіпсіздік тексерісінен өтеді және вирустар мен жасырын қауіптерден таза.

- 🔗 Ресми дереккөз: Тек Pin Up ресми сайтынан жүктеңіз.

- 💳 Қауіпсіз төлемдер: Қаржылық транзакцияларды қорғау үшін деректерді шифрлау қолданылады.

- ⚡ Жаңартулар: Қосымша тұрақты түрде жаңартылып, жаңа мүмкіндіктер қосылып отырады.

- 🔒 Деректерді қорғау: Барлық пайдаланушы деректері шифрланған түрде сақталады.

- 🛡️ Сенімді қолдау: 24/7 қолдау қызметі кез келген сұрақтарға жауап береді.

Осы ұсыныстарды орындау арқылы сіз Pin-Up KZ қосымшасын Android құрылғыңызға қауіпсіз түрде жүктеп алып, қолданбаның тұрақты жұмысын қамтамасыз ете аласыз.

Жүйелік талаптар

Pin-Up Casino қосымшасын қолданбаны қиындықсыз пайдалану үшін құрылғыңыздың минималды жүйелік талаптарға сәйкес екеніне көз жеткізіңіз.

| Талаптар | Минималды |

| ОЖ | Android 6.0 |

| Процессор | 1.2 ГГц 4 ядролы |

| Жедел жады (RAM) | 2 ГБ |

| Бос орын | 100 МБ |

| Экран ажыратымдылығы | 800×480 |

| Интернет байланысы | 3G |

Pin Up Казиноны тек ресми сайттан ғана жүктеуге болатынын ұмытпаңыз. Бұл сіздің деректеріңіздің қауіпсіздігін және құрылғыңызды жалған файлдардан қорғауды қамтамасыз етеді.

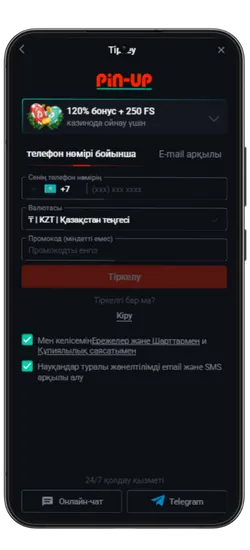

PinUp қосымшасы iOS үшін

iOS құрылғыларында Pin Up Casino Safari браузері арқылы жұмыс істейді және App Store жүктеуді қажет етпейді. Біздің қосымша әзірлену үстінде, бірақ қазірдің өзінде оны басты экранға қосып, жылдам қол жеткізуге болады. Бұл әрекетті қалай орындау керектігін төмендегі нұсқаулықтан қараңыз.

-

Ресми Pin Up сайтына өтіңіз

Safari браузерін iPhone немесе iPad құрылғысында ашып, ресми сайтқа кіріңіз.

-

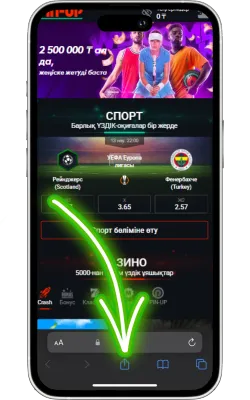

«Бөлісу» түймесін басыңыз

Safari экранының төменгі бөлігінде «Бөлісу» (жоғары көрсеткі бар төртбұрыш) белгішесін басыңыз.

-

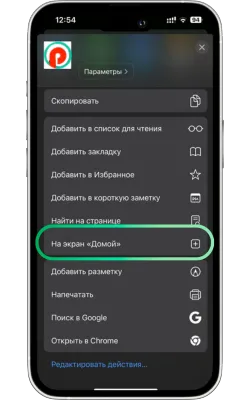

«Басты экранға қосу» опциясын таңдаңыз

Менюді төмен айналдырып, «Басты экранға қосу» түймесін басыңыз.

-

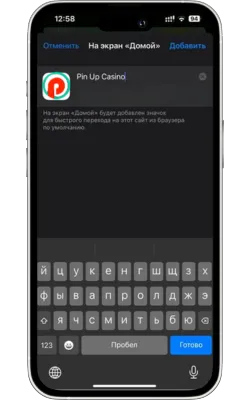

Атауын енгізіп, растаңыз

Жаңа белгіше үшін атауды енгізіңіз (мысалы, «Pin Up Casino») және «Қосу» түймесін басыңыз.

-

Pin Up Casino-ны ашыңыз

Экранда Pin Up белгішесі пайда болады. Оны басып, қосымшаны іске қосыңыз. Егер сіз әлі тіркелмеген болсаңыз, тіркеліп, ойынды бастаңыз.

Жүйелік талаптар

Pin-Up Casino веб-қосымшасының құрылғыда дұрыс жұмыс істейтінін тексеру үшін төмендегі минималды талаптармен танысыңыз.

| Талаптар | Минималды |

| iOS нұсқасы | iOS 11.0 |

| Құрылғы | iPhone 6 |

| Жедел жады (RAM) | 1 ГБ |

| Диск кеңістігі | 100 МБ |

| Интернет байланысы | Wi-Fi, 3G |

Pin Up қосымшасы iOS үшін әзірлену үстінде және жақында қолжетімді болады. Қазіргі уақытта Safari арқылы мобильді нұсқаны пайдалана аласыз – төмендегі батырманы басып, ойындар мен ставкаларға жылдам қол жеткізіңіз.

Қауіпсіздік және лицензия

Қосымша Кюрасао Ойын Комиссиясының лицензиясымен жұмыс істейді (лицензия нөмірі: OGL/2024/580/0570). Бұл халықаралық қауіпсіздік стандарттарына сәйкес келетінін және әділ ойынды қамтамасыз ететінін дәлелдейді. Пайдаланушылардың жеке деректерін және қаржылық транзакцияларын қорғау үшін заманауи шифрлау технологиялары қолданылады.

- 📜 Лицензия: Ресми тіркеу және құмар ойындарды реттеу

- 🔒 Шифрлау: SSL протоколы арқылы деректерді қорғау

- ⚖️ Заңдылық: Халықаралық қауіпсіздік талаптарына сәйкестік

- 🎰 Әділдік бақылауы: Сертификатталған кездейсоқ сандар генераторын пайдалану

- 🛡️ Жауапты ойын: Өзін-өзі шектеу құралдары

Pin-Up қауіпсіз ойын ортасын қамтамасыз етіп, қаржылық операциялардың сенімділігін сақтайды.

Қосымша арқылы депозиттер мен қаражатты алу

Pin-Up қосымшасында ыңғайлы және қауіпсіз төлем әдістері қолжетімді. Барлық төлемдер лезде өңделеді, ал комиссия жоқ.

| Төлем әдісі | Мин/Макс салым |

| Visa | 600 KZT / 500 000 KZT |

| MasterCard | 600 KZT / 500 000 KZT |

| Ұялы оператор | 600 KZT / 130 000 KZT |

| Vouwallet | 2 500 KZT / 1 100 000 KZT |

| Piastrix | 600 KZT / 400 000 KZT |

| BinancePay | 2 500 KZT / 23 000 000 KZT |

| Solana | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

| Bitcoin (BTC) | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

| Ethereum (ETH) | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

| Dogecoin (DOGE) | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

| Litecoin (LTC) | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

| Toncoin (TON) | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

| TRON (TRX) | 1 KZT / 450 000 000 KZT |

Қосымша арқылы жылдам қаражат шығару мүмкіндігі бар — ұтысты небәрі бірнеше минут ішінде алыңыз. Төменде қаражатты шығару шарттары көрсетілген.

| Төлем әдісі | Мин/Макс шығару |

| Visa | 3 000 KZT / 1 500 000 KZT |

| MasterCard | 3 000 KZT / 1 500 000 KZT |

| Ұялы оператор | 3 000 KZT / 1 500 000 KZT |

| Perfect Money | 3 000 KZT / 500 000 KZT |

| Bitcoin (BTC) | 7 000 KZT / 5 000 000 KZT |

| Ethereum (ETH) | 7 000 KZT / 5 000 000 KZT |

| Dogecoin (DOGE) | 7 000 KZT / 5 000 000 KZT |

| Litecoin (LTC) | 7 000 KZT / 5 000 000 KZT |

| Toncoin (TON) | 7 000 KZT / 5 000 000 KZT |

| TRON (TRX) | 7 000 KZT / 5 000 000 KZT |

Төмендегі батырманы басып, Pin Up Казиноны телефоныңызға тегін жүктеп алыңыз және барлық ойындарға, ставкаларға және бонустарға қол жеткізіңіз.

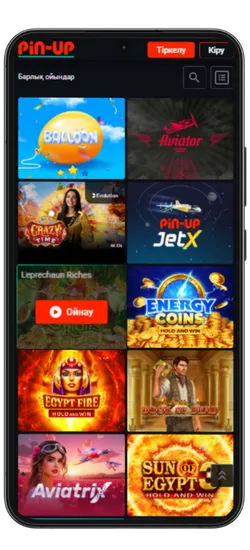

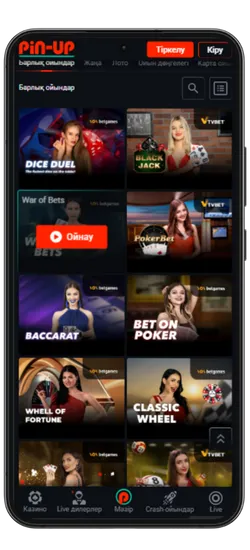

Казино ойындары

Pin-Up қосымшасында 70-тен астам әлемдік провайдерлерден 10 000+ ойын қолжетімді. Классикалық үстел ойындары, заманауи слоттар және Қазақстан ойыншыларына арналған эксклюзивті әзірлемелер ұсынылады. Үлкен ұтыстары бар слоттардан бастап, тірі дилерлермен ойындарға дейін бәрі бар.

Казино ең танымал ойындарды біріктірді, соның ішінде Fruit Party, Book of Ra және Рулетка мен Блэкджек сияқты классикалық ойындар бар. Барлық ойындар жоғары сапалы графикамен, жылдам жауап беруімен ерекшеленеді және телефон арқылы кез келген уақытта қолжетімді.

Онлайн-казино қосымшасында 8 негізгі бөлім бар:

| Категория | Сипаттама |

| 🎰 Слоттар | 9 165-тен астам автомат, түрлі тақырыптар, ұтыс жолдары мен бонустар |

| 💥 Краш-ойындар | 70 жылдам ойын, соның ішінде танымал Aviator |

| 🃏 Үстел ойындары | Классикалық ойындар – Блэкджек, Покер, Баккара және басқалар |

| 🎥 Тірі дилерлермен ойындар | 420-дан астам тірі дилерлермен ойындар |

| 🎯 Лотереялар | Лезде ұтыс беретін ойындар |

| 🏆 Джекпот ойындары | Үлкен джекпоттары бар слоттар, соның ішінде прогрессивті джекпоттар |

| 🃏 Видеопокер | Слоттар мен покердің ерекше үйлесімі |

| ⭐ Арнайы ойындар | Тек Pin Up-та қолжетімді эксклюзивті ойындар |

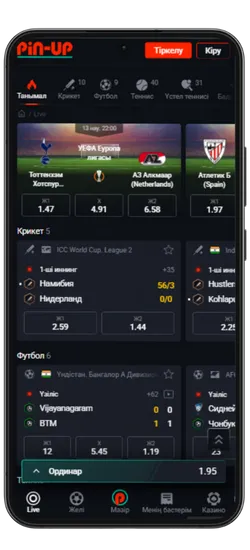

Спорттық ставкалар және виртуалды спорт

Қосымшада спорттық және виртуалды оқиғаларға ставка жасауға болады. 51 түрлі спорт түрі және күнделікті 3000-нан астам оқиға ұсынылады, сондай-ақ танымал киберспорт турнирлері бар.

- ⚽ Кең спорт түрлері – Футбол, баскетбол, теннис, бокс, хоккей және т.б.

- 📈 Live-ставкалар – Матч кезінде болжам жасап, коэффициенттердің өзгеруін бақылаңыз.

- 💰 Жоғары коэффициенттер – Ең тиімді ставкалар.

- 🎟️ Экспресс-ставкалар – Бірнеше оқиғаны бір купонға біріктіріп, ұтысты көбейтіңіз.

- 🔢 Икемді форматтар – Дробтық, ондық және американдық коэффициенттерді қолдайды.

Киберспорт пен виртуалды ставкалар тәулігіне 24/7 қолжетімді. Ең танымал дисциплиналар ұсынылған: Dota 2, CS:GO, Valorant, PUBG және басқалары. Сонымен қатар, виртуалды спортқа футбол, баскетбол және жарыстардың шынайы симуляциялары кіреді. Ставкалар лезде өңделеді, ал нәтижелер дәстүрлі спортқа қарағанда жылдам жарияланады.

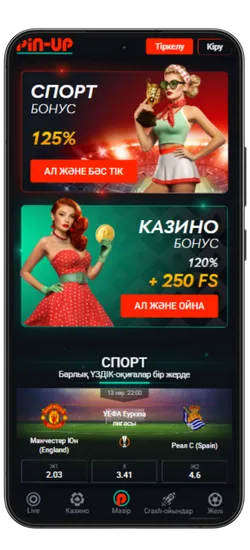

Бонустар мен Акциялар

Pin-Up қосымшасын жүктеген Қазақстан ойыншылары эксклюзивті бонустар мен акцияларға қол жеткізе алады. Қош келдіңіздер бонустары, кэшбэк, тегін айналымдар және басқа да сыйақылар ұсынылады, ойын балансын арттыруға көмектеседі.

- Қош келдіңіз бонусы: Спорттық ставкалар үшін алғашқы депозитке 125% немесе казино үшін 120% + 250 FS.

Максималды бонус – 2 500 000 KZT. Вейджер: x50. Ойнау мерзімі – 72 сағат. - PROMO773 промокоды: Бірінші депозит бонусын 150%-ға дейін арттырады.

- Апта сайынғы кэшбэк: Жоғалған қаражаттың 10%-ға дейін қайтарымы.

Кэшбэк мөлшері:

– 5% – 20 000 KZT жоғалтқанда

– 7% – 100 000 KZT жоғалтқанда

– 10% – 400 000 KZT жоғалтқанда

Максималды кэшбэк – 1 000 000 KZT. Вейджер: x5. Ойнау мерзімі – 72 сағат. - Сыйлық қорабы: Әр 30 000 KZT ставка үшін кездейсоқ сыйлықтар беріледі.

Марапаттар: ақшалай сыйлықтар, бонустар, pincoins және тегін айналымдар.

Жарамдылық мерзімі – 10 күн. - 100% экспресс бонус: Экспресс ставкалардағы ұтысты 100%-ға дейін арттыру.

Минималды ставка – 1 600 KZT. Минималды коэффициент – 1.3.

Максималды бонус – 2 000 000 KZT. - Қос дүйсенбі: Екі есе ставкалар билеттерін алыңыз.

Әр дүйсенбіде кездейсоқ 3 000 купон таңдалып, олардың ұтыстары екі еселенеді.

Минималды ставка – 1 000 KZT. Минималды коэффициент – 1.4. - Экспресстердегі кэшбэк: Жоғалған экспресс ставкалардан 55%-ға дейін қайтару.

Минималды ставка – 2 000 KZT. Минималды коэффициент – 1.50. - Күннің экспресі: Коэффициенті 15%-ға арттырылған дайын экспресстер.

Күн сайын «Линия» бөлімінде қолжетімді. - Cash Out: Ставка бойынша ұтысты ертерек шығару мүмкіндігі.

Ординарлар мен экспресстер үшін қолжетімді.

Промо код:

Акциялар үнемі жаңартылып отырады, жаңа ұсыныстар қосылады. Жаңалықтарды бақылаңыз, тиімді бонустарды жіберіп алмаңыз!

Эксклюзивті бонустар мен акцияларды алу үшін Pin Up ресми сайтын жүктеп алыңыз. Бонусты дәл қазір пайдаланып, Pin-Up-та ұтып алыңыз! 🚀

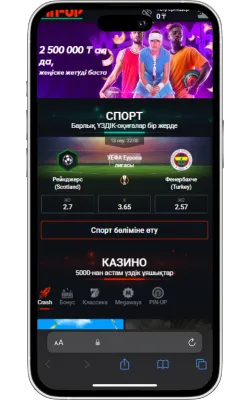

Pin-Up қосымшасының скриншоттары